Raising the ba: Wildlife and the Ancient Egyptian Book of the Dead

By Ruth D’Alessandro, The Wildlife Gardener The Wildlife Gardener is partial to a bit of papyrology. Egypt old and new has been a substantial part of my life and I can never tire of looking at tomb paintings and hieroglyphics. So we were particularly thrilled when Ancient Egyptian Book of the Dead: Journey through the Afterlife exhibition opened at The British Museum.

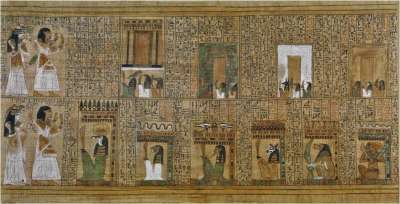

On a grey January day, heads fuzzy with the malaise of an overlong festive season and desperate for some culture, we headed for Bloomsbury with our wise and wonderful friend Sara, to the fabulous womb-like exhibition space that has been created within the British Museum’s historic Reading Room. So what has The Book of the Dead got to do with wildlife? Apart from mummifying cats and depicting their gods with jackal and falcon heads, were the Egyptians great observers of fauna and flora? The answer is yes: exquisite observers, and often with a liberal pinch of humour too. Observations of nature are scattered liberally throughout the papyri: nature lovingly depicted and recorded. A Book of The Dead is a sort of Rough Guide to the Underworld, a papyrus scroll of spells and pictures placed in a tomb with the mummy. It was designed to guide the soul (ba) of the dead person through the trials of the netherworld to the afterlife where, if successful, body and soul would reunite and live forever. Each body had its own Book of the Dead: a lovingly scribed, bespoke one if you were royal or rich, or a less posh’off the peg’ version which would be ready scribed but with gaps in which to drop the deceased’s name. The adventures were pick’n’ mix : different trials awaited different souls in different Books. The winged ba would go off and undergo the trials, using the spells in the Book of the Dead, while the temporal mummy remained in the tomb preserved and protected by amulets, charms and statues until the ba came back triumphant (picture above). A terrifying landscape awaited the ba: impossibly high mountains, rivers and lakes where terrible chimeras hung about with nets to catch the unwary, numerous huge gates and doors guarded by the grotesque deities of the underworld:

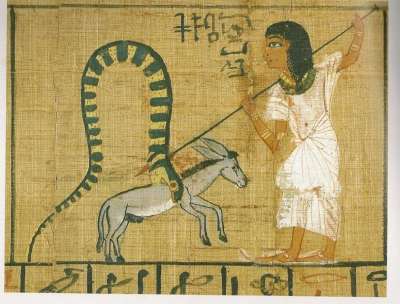

At each gate the ba was instructed to say:’I know you and I know your names’ (an ancient equivalent of’I know where you live’?) before naming each one from the Book. When it needed to be able to turn into a swallow or a falcon to fly over a high mountain, the Book gave a spell enabling the ba to do just that. A big snake might try to bite your ass:

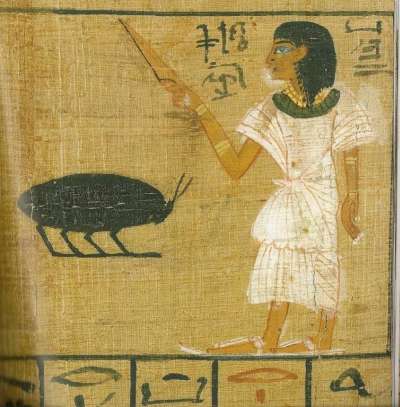

A mighty weapon could be conjured up to kill the snake. If you were menaced by a giant eight-legged flesh-eating beetle:

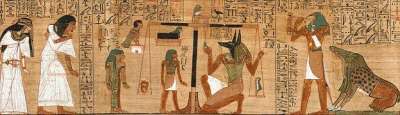

…there was a spell to shoo that away too. But even after passing the Boschian tests of the netherworld, the final challenge came when the dead person’s heart was weighed against the feather of truth. If the heart was free of evil, the ba and body were reunited in the afterlife. If not, their heart was eaten by the hideous’Devourer’ a beast with a crocodile’s head, a lion’s body and a hippo’s bottom, and that was the end of that. For eternity.

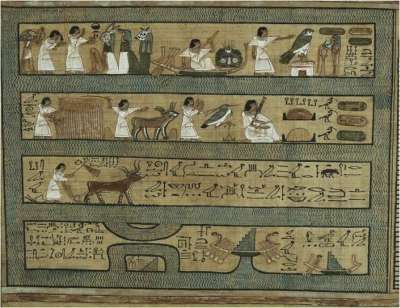

This is not just an afterlife. This is an Ancient Egyptian afterlife. The deceased was even offered a choice of activities. He/she could accompany the sun god Ra in his boat sailing across the sky by day and through the netherworld by night, or choose to abide in The Field of Reeds (cf. also The Elysian Fields and the opening scene of Gladiator), a landscape like fertile Egypt itself. Look at the exquisite nature illustration here:

Then, in the final room was the denouement to and the point of the whole exhibition: the 37-metre-long Nesitanebisheru’s Book of the Dead. With barely any museum notes to accompany it, you found yourself’reading’ and understanding Nesitanebisheru’s Book as you moved along its 37 metre length. The layout of the exhibition up until now had taken us on the journey using artefacts and fragments of different Books of the Dead to tell the story. Suddenly the winged bas, the snakes, the cattle, the figures, the crocodile-headed monsters and the wetland boats all made perfect sense as we followed Nesitanebisheru effortlessly into the afterlife. The Junior Wildlife Gardeners were enthralled. We all felt like Egyptologists. We had been educated, absorbed and had hardly noticed it happening. That’s what a world-class exhibition should do. British Museum ” you’ve done it again!

- Spurn Spawn! - 26th February, 2014

- Bluebells on wheels: axles of evil? - 2nd February, 2011

- Raising the ba: Wildlife and the Ancient Egyptian Book of the Dead - 8th January, 2011

Wonderful introduction to the Egyptian Book of the Dead. I am familiar with the Tibetan Book of the Dead and notice similarities. Interesting that animals were seen as enemies or at least obstacles. And their notion of afterlife, absolutely wild.