Darwennui, or ‘Humboldt from the Blue’

By Ruth D’Alessandro, The Wildlife Gardener There’s been an awful lot of Darwin about this year; La famille Wildlife Gardener initially embraced the 200/150 Darwin celebrations with a passion. We’ve watched David Attenborough, Andrew Marr and Jimmy Doherty, we’ve read Alan Moorehead’s fabulous Darwin and the Beagle in instalments at bedtime, we’ve visited the Natural History Museum and the Genesis Expo to explore the other side of the evolution/creation argument.

We’ll soon be revisiting the revamped birthplace of On The Origin, Down House. Junior Wildlife Gardener no 1 is no stranger to Down House. As is the way of new parents with a first-born we took her there when she was 18 months old hoping to give her an early introduction to evolutionary biology. All she wanted to do was roll up and down the disabled ramp. But I can’t help feeling that Darwennui is now setting in. I’ve heard and read enough about the Galapagos Islands, the birds (Finches eh? Seen one, seen’em all!), Captain Fitzroy, the Victorian family life with its loves, losses and earthworms. Comfortable in my beliefs that there is no conflict between religion and evolution, I’m now as bored of discussing the controversy as I am of talking about house values. In the words of Bonnie Tyler, I’m Holding Out For a Hero: someone else to be fascinated by. So as I was putting Darwin and the Beagle back on the bookshelf, I noticed a 1973 book I bought from a jumble sale but haven’t yet read: Humboldt and the Cosmos by Douglas Botting. Who was this Alexander von Humboldt?

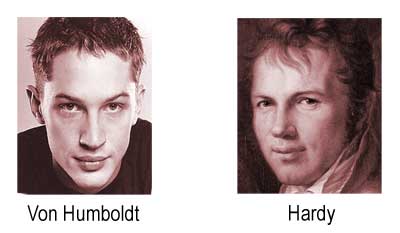

Mmm. He’s easy on the eye. But is he interesting? Oh yes. He was a scientist of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, an explorer and a diplomat, the last truly Universal Man, considered second only to Napoleon in influence at the time. His name appears on maps of the five continents: over 1000 places in the world bear his name, even a crater on the moon! Of fauna and flora: a penguin, a squid, a hog-nosed skunk, an Amazon River dolphin, a lily, an orchid, a bladderwort, a cranesbill, an oak and a willow are all humboldtii/humboltiana (except the Humboldt squid, which is Dosidicus gigas). In fact, if he hadn’t done his stuff in the 50 years before On The Origin of Species (Humboldt died in 1859, the year of On The Origin’s publication) 2009 probably wouldn’t be as saturated with Darwiniana as it is. Humboldt is credited with initiating the great explosion of knowledge that allowed Darwin to expound his theory. Alexander von Humboldt was born in 1769 to a wealthy Prussian family, where science was considered an unworthy subject for someone of such social standing. After a short career as a mining official, Humboldt set off to explore South America. The volume of scientific data he collected during his five-year expedition laid the foundations for modern physical geography and his botanical studies established plant geography. He climbed Mount Chimborazo, then the highest known mountain in the world, and held that record for the next thirty years – time that he spent publishing a 23-volume work about South America. A charming, clever and generous man, Humbolt became friend and adviser to President Jefferson when he visited the US on his way home from South America in 1804. Not only radical politically, and in contrast to Darwin’s familial heterosexuality, Humboldt was a passionate gay man who, following a two-year affair with a Prussian soldier Reinhard von Haeften, lived with von Haeften and his wife during the first six months of their marriage. He had a close relationship with Aimé Bonpland, the French botanist who accompanied him to South America, and in his writings he lovingly described the masculine beauty of the South American Indians.

Although Humboldt’s homosexuality was widely acknowledged in his lifetime (he was active in Berlin’s gay subculture), his sister burned all his love letters, so we’ll never know the details first hand. Humboldt set off on an expedition to Siberia when he was in his sixties, discovering crab apples, the true height of the Central Asian plateau and diamonds in the Ural mountains. As a lifelong, compassionate radical, he was deeply critical of the treatment of the Russian poor under Czar Nicholas I. In the last years of his life, Humboldt completed his greatest work, Cosmos – his vision of the nature of the world, and the unity to be found within nature’s complexity. Humboldt saw nature as a whole and Man as part of that whole. His aim was to communicate the intellectual excitement of scientific research as part of a country’s wealth. On religion, Humboldt wrote:

All religions offer three different things ” a moral rule, the same in all religions and very pure, a geological dream, and a myth or legend. The last element has assumed the greatest importance.

So why has the 150th anniversary of Humboldt’s death passed unremarked here in the UK? Few of us have really heard of him. Could it be because Humboldt was Prussian, and not a home-grown science hero? Guess what? Foreigners can be scientists too! And some of their lives and works are as fascinating as that of the ubiquitous Charles Darwin. Perhaps Humboldt’s biggest missed trick was not to upset the Church: no publicity is bad publicity. Perhaps we in the UK are just not that interested because he was German. Could our German Naturenet readers please let us know if Humboldt is as revered in his own country as Darwin is here? What a fantastic film could be made of Alexander von Humboldt’s life: The Motorcycle Diaries meets Brokeback Mountain meets Dr Zhivago. Tom Hardy should play Humboldt.

I’m so looking forward to reading Humboldt and the Cosmos, probably aloud to the Junior Wildlife Gardeners at bedtime. I do not shy away from trying to explain difficult or controversial concepts to my children, whatever age they are, especially as they ask the questions. JWG1 was captivated by Darwin and the Beagle and begged to explore Darwinism further. If Humboldt captures the imagination as much as Mr Darwin did, I fully expect to be explaining the principles of physical geography, finding a picture of a hog-nosed skunk and answering the question ‘Mummy, what’s a homosexual?’

- Spurn Spawn! - 26th February, 2014

- Bluebells on wheels: axles of evil? - 2nd February, 2011

- Raising the ba: Wildlife and the Ancient Egyptian Book of the Dead - 8th January, 2011

Fascinating stuff. All the media have jumped on the Darwin anniversaries bandwagon but it does nothing to diminish Darwin’s significance, in my view. My advice is to watch less television. As for making a movie about Humboldt, just imagine what a distorted picture would ensue in the chase for ratings, in view of his personal life you have documented here. Just for the record, Darwin himself described von Humboldt as ‘the greatest scientific traveller who ever lived’.

Yes, ghostmoth, if TH is unavailable. And perhaps Daragh O’Malley (Sharpe’s sidekick) for Aime Bonpland, though he’s a bit craggy now.

Fascinating! I was vaguely aware of Humboldt but only because of the penguins named after him. Good casting for the Humboldt movie, although there’s definitely a look of David Morrissey about him.

Steve – the book had a very detailed foreword…and for everything else, there’s Wikipedia.

I completely agree, let’s move on from the evolution vs religion discussion/controversy and focus on more pertinent issues like climate change!

Thousands of species are going extinct, some of them may hold the key to our very survival, and we have nothing better to do than be upset by differing points of view?

Let’s move foreward!

Bill

Ruth, you know all that before you’ve read the book?

Fascinating stuff!